Background: The Cleveland Heights Police Department has launched a Citizens Police Academy for members of the community who are interested in learning more about how the police department operates. The first course runs 6-9 p.m. on Monday and Tuesday evenings, for seven weeks beginning Aug. 11 and ending Sept. 30, 2014. This blog post is one of a series about my experience in the program. Click here for the full series.

On paper, Week Four of the Cleveland Heights Citizens Police Academy looked like it should be fun. On Monday night, the agenda included time with the K-9 unit, bomb squad and the SRT Team (it stands for Special Response & Tactics, but most people still call it SWAT).

All three hours of Tuesday – plus an extra 45 minutes of overtime – were spent at the city’s shooting range, located in a nominally marked building on Superior Road just south of Mayfield.

This was the week when the police department got to show off its most impressive hardware to an interested and captive audience.

By the time it was over, I was depressed and angry. It’s taken me several days to think it through.

The Citizens Police Academy experience is not about turning citizens into police officers or auxiliary patrols. (Graduates of the Shaker Heights Citizens Police Academy do actually patrol business districts; if asked to do the same, I would decline.)

The police department wants us to have a better understanding of how it works and what it takes to protect and serve in the 21st Century. Most clearly, the department wants us to experience its deep commitment to providing police officers with high quality training – and lots of it.

Capt. Geoffrey Barnard, commander of the Cleveland Heights Police Academy and our primary instructor, said: “When bad things start happening quickly, you’ll always revert to your training.”

As an example, he has played dash-cam video of the 2013 ambush of Middlefield, OH police officer Erin Thomas – a graduate of the Cleveland Heights Police Academy. She was shot in what began as a routine traffic stop.

With her left hand hit by a bullet and useless, her training kicked in. She emptied her gun, told herself she wasn’t going to die, then she continued to fight, Barnard narrated. With one working hand, she took over the radio to support her partner in any way she could until the shootout was over.

“When bad things start happening quickly,” Barnard repeated, “You’ll always revert to your training.”

I provide this background because we didn’t actually diffuse bombs or ride along with the SWAT team. We aren’t being trained; we’re learning how others are trained.

We did get to make nice with two of the department’s three police dogs – Argos and Rocky – but we didn’t spend anywhere near enough time at the shooting range that they would actually let us shoot guns.

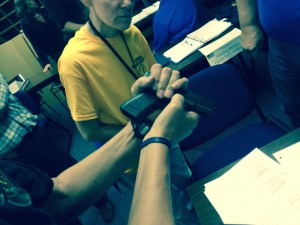

Which was fine with me. I’d never handled a real gun before. Now I have. I’ve loaded and unloaded both a revolver and semi-automatic pistol. I know now that when you pull a magazine out of a semi-automatic, the odds are good that there’s still a bullet in the chamber – a detail that can kill you or someone else if overlooked. It’s as much direct experience with guns as I ever hope to have.

Among friends and family, I’ve been flippantly referring to the whole experience as Police Camp, and it wouldn’t be inaccurate to say that so far it’s been an extended show-and-tell.

But if that’s all it was, I wouldn’t be beating around the bush right now about why I suddenly found myself so overwhelmed and uncomfortable when Det. Martin Block entered the police academy classroom fully equipped in SRT gear.

Block could have come out of Central Casting for the appearance. He’s intense and steel-eyed, with a Steve McQueen jawline. He’s a U.S. Marine who, we were told, was serving in Beirut when the U.S. barracks there were bombed in 1983, killing 241 servicemen.

There is a certain amount of theater built into the SRT Team. Every piece of equipment is designed not just to be brutally functional but also to intimidate – from the black van the team rides in (more typically, members respond in squad cars, where they carry their own SWAT gear) to the strobe-equipped shield that’s the first thing through a door on a raid.

“We don’t fight fair,” Barnard said. “We want to make sure that every advantage is on our side, and that every disadvantage is on the bad guy’s side.”

It was all very impressive. And depressing.

The Bomb Squad too. We were shown pipe bombs (sans explosives) with gravity switches and timed activators. We learned the difference between an incendiary and explosive device (incendiaries burn; encase them and they explode) and learned how astoundingly simple it is to make either one using ingredients you probably have in your home right now.

I should feel good that our police department is so well equipped – and that its people are demonstrably so well trained.

I recognize the need. And while you can argue (I have) that some of these specialized capabilities ought to be funded regionally rather than locally, the sad reality is that even as threats to public safety grow larger and more exotic, the number of cities willing to fund SWAT teams, bomb squads, K-9 units and even regular shooting practice is shrinking.

According to our instructors, the City of Cleveland doesn’t even have an indoor shooting range, which means Cleveland Police don’t practice shooting in low-level lighting – the most likely condition when shootings occur.

While Cleveland Heights police officers shoot 60 practice rounds a month, Cleveland’s, we were told, shoot only 30. And Ohio now requires only 25 rounds for its annual firearm requalification. That’s right: Just 25 shots, once a year.

Why? Money. As crime rates rise and criminals become more dangerous than ever, many cities can’t afford bullets for target practice. Sure, the federal government will provide them with high-tech military hardware. But what happens when you skimp on training?

Here, in my opinion, are three recent answers to that question:

- Cleveland police fire 137 shots, killing two

- Doubts case on account of black man killed in Walmart

- Unarmed black teenager shot in Ferguson, MO

By all accounts, we are losing the war. There are more bad guys with bigger weapons doing worse things than ever before. And our society has so fetishized guns and gun rights that every last piece of ammunition gets snapped up as soon as it leaves the manufacturer. In the last few years, the price of bullets has tripled – if you can find them at all.

In Cleveland Heights, supplies for the police academy have to be ordered 6 months in advance.

Elsewhere, they just cut back on training.

Ohio Legislators vote to reduce little things like prison staffing (see T.J. Lane) and the competence of law enforcement officers who venture into public every day with loaded weapons and a charter to use them. And in the next breath, they tell us we’re still paying too much in taxes.

My hostile reaction to the past week’s curriculum has everything to do with that.

It’s inevitable that reports will only increase about law enforcement officers shot while simply doing their jobs; and civilians being killed in misunderstandings with police officers. I’m certain of this – more now than two weeks ago.

All that hardware, all that gun talk was about a situation that’s all too real and becoming more dangerous every day (remember Jim Brennan).

And yet, if being safe means being prepared to kill someone and walking around with a loaded gun, then I’m choosing to live in denial. This is why we have police.

But seeing the full range of advanced weaponry; learning about the many specialized forms of police training; seeing the care with which the city’s shooting range is maintained; handling bullets – even dummies with their primers removed; hearing from officers who have had violent confrontations with offenders; internalizing that police work is a career spent with one foot in squalor – all of it crashed my idyllic world.

I should be relieved that our city has dug in its heels against the downward trend. Unlike what appears to be the case in Ferguson, MO, I should be glad that our cops haven’t traded in good training for even more federally funded paramilitary equipment.

I should take solace in the fact that I’ve never actually seen the bad-ass SRT van in action.

I mentioned this to one of my classmates, who lives in the city’s less idyllic north end.

“Really?” he said. “I’ve seen it three times. Twice on my own street.”

Leave a Reply