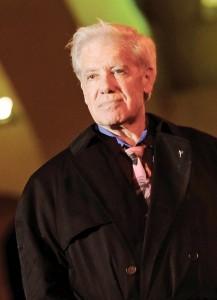

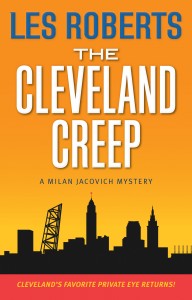

Mystery writer Les Roberts, a Chicago native, lived in Cleveland Heights for almost 20 years after a long career as a Hollywood television writer and producer. His newest novel, The Cleveland Creep (hardcover / $24.95 / 264 pages) is #15 in a series featuring fictional Slovenian American private investigator Milan Jacovich (pronounced MY-lan YOCK-ovich), a former Kent State University football player and ex-cop with a taste for klobasa sandwiches and Stroh’s beer and a knack for finding trouble on the streets of Cleveland. The fictional character of Milan lives in an apartment on Cedar Hill in Cleveland Heights directly across from the Mad Greek restaurant.

Mystery writer Les Roberts, a Chicago native, lived in Cleveland Heights for almost 20 years after a long career as a Hollywood television writer and producer. His newest novel, The Cleveland Creep (hardcover / $24.95 / 264 pages) is #15 in a series featuring fictional Slovenian American private investigator Milan Jacovich (pronounced MY-lan YOCK-ovich), a former Kent State University football player and ex-cop with a taste for klobasa sandwiches and Stroh’s beer and a knack for finding trouble on the streets of Cleveland. The fictional character of Milan lives in an apartment on Cedar Hill in Cleveland Heights directly across from the Mad Greek restaurant.

In The Cleveland Creep, a simple missing-person case gets complicated when a collection of voyeuristic videos leads Milan to an organized crime connection–and a dead body. In the following book excerpt, Milan first meets Savannah Dacey, a west side mother whose son Earl has disappeared but has left some very provocative clues:

When a child goes missing, there is nothing more frightening, tragic, or terror-inducing for the distraught parent. Most never give up hoping. That’s how it was for my new client, Savannah Dacey—even though her “child” was a grown man in his twenties.

Savannah is one of the most atmospheric cities in America, on the Atlantic coast in Georgia—full of beautiful old buildings, hanging moss, eccentric natives, and weeping willows. Its summertime humidity can knock you off your feet, and it’s been the subject of a series of books, including one that wound up a Clint Eastwood movie. A river with the same name, Savannah, runs nearby. Additionally, Savannah is the name of a woman who does stand-up news at the White House for NBC television, Savannah Guthrie. Like her, most women named Savannah are attractive and as tropical-looking as their names—or at least they seem more that way than if they’d been christened Sadie or Gertrude.

But Savannah Dacey didn’t fit the name in any way. She’d sounded like a sad sack when she made the phone appointment, and whiny to boot, and she looked like a sad sack, too. She was close to fifty, and looked ten years older. Her fingers were thick as bratwursts, fingernails polished the vivid crimson women stopped wearing in 1972. Her hair had been “done” and dyed an improbable red by someone in a low-rent beauty shop. Her eyeglasses, also of a long-gone era, were bright green, shaped like cat’s eyes, with ungainly rhinestones twinkling in each corner. Her forehead and upper lip were shiny with perspiration, and half-moon sweat stains appeared at the underarms of her short-sleeved white blouse. Her wrinkled, inexpensive peasant skirt made her appear as if she’d walked in the heat and humidity from her West Park home all the way to my office on the west bank of the Flats.

How anyone named “Savannah” wound up in Cleveland is anyone’s guess; it’s not a Savannah kind of town. But I’ve met women with even more exotic names, as you’ll learn.

“It’s kind of you to see me on such short notice, Mr. Jacovich,” she said. She’d phoned me the day before and had mispronounced my last name. If it gives you trouble, just sound it out properly with the J sounding like a Y—Yock-o-vitch. It’s hard to say, I think, which is why I christened my private investigation business Milan Securities after my first name. Put the American slant on it—My-lan—and don’t say it the way you’d pronounce the name of an Eastern European, or the Italian city noted for its fashion shows and its opera house. I’d gently corrected her on the phone, and now Savannah said my name carefully, as if she’d been practicing.

“It’s kind of you to see me on such short notice, Mr. Jacovich,” she said. She’d phoned me the day before and had mispronounced my last name. If it gives you trouble, just sound it out properly with the J sounding like a Y—Yock-o-vitch. It’s hard to say, I think, which is why I christened my private investigation business Milan Securities after my first name. Put the American slant on it—My-lan—and don’t say it the way you’d pronounce the name of an Eastern European, or the Italian city noted for its fashion shows and its opera house. I’d gently corrected her on the phone, and now Savannah said my name carefully, as if she’d been practicing.

Her son, twenty-eight-year-old Earl Dacey, was missing. He had left the house six days earlier and hadn’t been heard from since. Now his mother wanted to know what had become of him. “He never stayed out all night in his life,” she moaned. “If he’s ever half an hour late getting home, he always calls me. Always. He’s a good boy.”

“Does he have a car?”

“An old crappy car,” she said. “A two-door blue Dodge from around 1985. He bought it himself last fall. I never axed him where he got the money.”

Axed him: fingernails on a blackboard. I’d been on the edge of the Earl Dacey disappearance for less than five minutes, and he was already an albatross around my neck. I said, “Is he someplace with a—” I paused, not wanting to say “woman.” I had no right to assume Earl’s sexual preferences. “With a lover?”

“He don’t date girls. He don’t have men friends, either. The best friend he has in the whole world is me.” Savannah said it proudly.

“Where does he work?”

“He don’t have a job right now.” She shifted her spreading backside in my visitor’s chair. “He never had a proper job. He don’t get along with people he don’t know. He’s shy.” Her eyes twinkled behind the cat’s-eye glasses. Maybe she was flirting with me; I hoped not.

“Does Earl have any hobbies?”

“No—he watches TV, an’ plays on his computer for hours at a time. He likes watching baseball.” Her round whey-face lit up as she glanced out my full-length windows across the Cuyahoga River to where the Indians play—Progressive Field is its official name now, although almost everyone in Cleveland still refers to it as what they called it when it opened in 1994, Jacobs Field, or more familiarly, “The Jake.” The ballpark and my office are on opposite sides of a peculiar, sometimes dangerous kink in the river known as Collision Bend—I’m always amazed that few Clevelanders know what it’s called.

“Does Earl play baseball?”

“Lord, no! He’s not very athletic.”

“Nothing else he likes?”

“Eating—spaghetti a couple times a week, or pizza or cheeseburgers. And he likes taking pitchers, too.”

The start of a headache thrummed against my eyeballs. Pitchers! I couldn’t correct my prospective client. Not only isn’t it my job, but half the people in Cleveland call a photograph or a painting a “pitcher,” not realizing a pitcher is a guy on the mound who accurately throws a ball ninety miles an hour at another guy with a big stick in his hand and dares him to hit it. “Pitcher” is also a vessel from which to pour milk, water, or Kool-Aid. But Savannah and lots of other people don’t even know how to pronounce “picture.”

I wasn’t overjoyed about my headache, either. I was getting lots of them—more than I used to. They weren’t blinding migraines that put me out of commission; they were more the essence of a headache. Maybe I was getting old. Sixty is the new forty, or so they say—and sixty was still almost a year ahead of me. I rubbed the back of my neck. “He likes taking pictures?”

“He never goes anywhere without his camera—or his videocam.”

“He has a videocam?”

She nodded. “I dunno what he films with it, but I guess he’s having a good time so I don’t even ask.”

“Did you contact the police?”

“Fer sure,” she said—another expression that quietly died in the late sixties. “I told them he was gone, but they didn’t have much interest.”

“He’s an adult. They assumed he’d left of his own accord.” I cleared my throat. “Maybe he has.”

“No way!” There was real emotion behind her whine. “He wouldn’t worry me like that unless he’s got to.”

I nodded. “It’s a hot morning, Ms. Dacey,” I said, more out of pity than anything else. “How about something cold to drink? A Pepsi, or a Mountain Dew?”

She was immediately interested. “Regular or diet?”

“Regular Mountain Dew, Diet Pepsi.”

“Eew, no diet anything. But I wouldn’t say no to a Mountain Dew,” she simpered. I got a Dew from my office-size refrigerator, painted to look like an old-fashioned Wells Fargo safe, and she poured it into a plastic glass I gave her from my bottom desk drawer.

I said, “Does Earl belong to a photography group or a camera club?”

She shook her head.

“Who does he take pictures of, then?”

“I don’t know. People? Maybe just buildings—or dogs or squirrels. He don’t show me his pitchers very often.”

“And he has no friends—even casual ones?”

“Earl isn’t so at ease with strangers. They scare him.” She examined me with an admiring frankness that weirded me out. “You’re a big guy—I bet you’ll scare him, too.”

“I’ll try not to,” I said. “So he doesn’t have a job or a girlfriend, he doesn’t spend time with friends. Where do I start looking for him, Ms. Dacey?”

“If I knew, I’d look there myself. That’s why I want to hire you.”

“That brings us around to money.” I told her how much I charged, half expecting her to turn pale and scurry from my office, because the whole country was struggling against a recession—but when someone has an important reason to want a private investigator on the job, they somehow get the money they need. Savannah took my quoted prices in stride. Her late husband, Earl’s father, had died eight years earlier, leaving her a handsome pension from his long career on the line at the Ford plant. Shortly thereafter she hired on as night manager of a family restaurant on Detroit Avenue, so it didn’t bother her to whip out her checkbook and write me a retainer.

“I want to start by looking at your house first,” I said.

“Earl’s not at my house.”

“No, but maybe I could find information that will help show me where I might look for him.”

She looked dubious but said it was okay.

“Will you be home in about an hour and a half? At noon?”

“Yeah, but I have to work tonight—I’ll leave at about four thirty,” she said, sneaking another fond glance out the windows. “This is a lovely office—such a nice view of downtown.”

It is a nice view of downtown. It makes me feel good just looking at it. The familiar downtown skyline is my town—or I’ve always thought so. Born and bred, and though I’ve traveled—two years in Vietnam being a military policeman was a large part of it—I’ve never wanted to move anywhere else. “Thank you, Ms. Dacey.”

She fluttered her eyelashes at me. “You can call me Savannah—um—Milan.”

Now we were on a first-name basis—in moments we would become lifelong buddies.

Her high heels clattered down the steps. I didn’t move until I heard her car start up and pull out of the lot. Then I breathed more freely.

I’m never comfortable with my clients. People at the end of their rope wouldn’t hire me if they weren’t under great stress. Still, I had sympathy for a mother whose son vanished, even if he was nearly thirty.

I created a new Earl Dacey file on my computer and typed in all his mother had told me. It didn’t even fill up one page. I feared this would be a long haul, because I had other active jobs on my calendar, the main one an assignment from a large warehouse on the East Side in which brand-new refrigerators, stoves, air conditioners, and giant TV sets were kept until the retail store called for them to be delivered. One of the warehouse employees was claiming workers’ comp and had been staying home from his job for the past six weeks, nursing what he swore was a very badly injured back from wrestling those heavy appliances out to a delivery truck. His bosses wanted to know if he really was disabled—so my assignment was to follow him around and see whether those supposedly misaligned vertebrae were truly keeping him from going back to work. I’d already seen him lug his heavy trash cans from his back door to the curb on garbage days, heft two cases of beer from his shopping cart to the back of his pickup at a Dave’s supermarket, and even struggle with a gigantic watermelon.

I had more written about him than I did about Earl Dacey—but with Earl I was just getting started. I wish I didn’t have to take Savannah’s case.

I guess I’m just a sucker for mothers who tremble on the edge of crying.

Excerpted from the book, The Cleveland Creep © 2011 by Les Roberts. This text may not be reproduced in any form or manner without written permission of Gray & Company, Publishers. The book is available at Northeast Ohio bookstores and online from Amazon.com. For more information about Les Roberts and his books, visit LesRoberts.com.

Leave a Reply